More stock NPCs for your Dungeons & Dragons game:

- A hulking paladin voiced in your best Patrick Warburton impression who uses the names of obscure polearms as expletives

- A ranger who aspires to be a fashion designer, and hunts rare beasts to obtain their hides and fur for use in dressmaking

- What initially appears to be a dwarven runecaster with a badger familiar, but it turns out it’s actually the badger who’s the runecaster, and the dwarf is her personal assistant

- A compulsively stealthy rogue who insists that all their thievery is in support of a sick relative; it’s not entirely clear whether there’s one sick relative or many involved, as the details change every time they tell it

- A bard outlawed from their home village after making a pun so terrible that it killed the blacksmith

- A swashbuckling fighter who enjoys lavish hospitality on account of their fearsome reputation, but is secretly just very skilled at stage combat and can’t actually fight their way out of a wet paper bag

- A star pact warlock with maxed out Bluff impersonating a cleric of a benevolent sun god

- A mysterious druid dwelling on the outskirts of town who everyone politely pretends not to notice is actually three dire raccoons standing on each other’s shoulders in a feathered robe

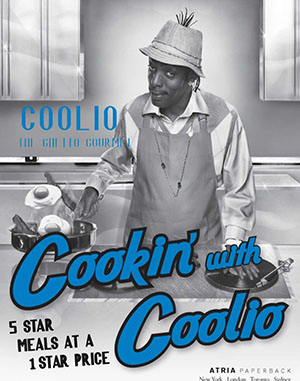

This book might be okay if it weren’t for Coolio’s insistence on referring to a tablespoon as a dime bag, and the publisher’s insistence on inserting what they seem to think is “rap talk” into each sentence.

'It really was the last time when the world was simple and small," sighed the US television writer Adam Goldberg a while back, explaining his decision to set his new sitcom, The Goldbergs, in the 1980s. What made that era different, he argued, was that the internet hadn't yet erased distance; your world consisted mainly of your immediate family and surroundings. But if you teleported back to Goldberg's world in 1985, I don't think it's his lack of web access you'd notice first. Like me, Goldberg is in his late 30s; in the 1980s, he was a child. "The 80s wasn't 'the last time the world was simple'," one commentator, Paul Waldman, chided on his blog. "The 80s was the last time your world was simple." The hazy memory of a simpler past is enormously powerful in politics: see the Tea Party, or the hate-nostalgia of the Daily Mail. But look closely at the era being praised, whether it's the 40s or the 90s, and you'll frequently find the praise-giver was about seven at the time. Unless you're eight, the world really has changed since you were seven. But possibly not as much as you have.

'It really was the last time when the world was simple and small," sighed the US television writer Adam Goldberg a while back, explaining his decision to set his new sitcom, The Goldbergs, in the 1980s. What made that era different, he argued, was that the internet hadn't yet erased distance; your world consisted mainly of your immediate family and surroundings. But if you teleported back to Goldberg's world in 1985, I don't think it's his lack of web access you'd notice first. Like me, Goldberg is in his late 30s; in the 1980s, he was a child. "The 80s wasn't 'the last time the world was simple'," one commentator, Paul Waldman, chided on his blog. "The 80s was the last time your world was simple." The hazy memory of a simpler past is enormously powerful in politics: see the Tea Party, or the hate-nostalgia of the Daily Mail. But look closely at the era being praised, whether it's the 40s or the 90s, and you'll frequently find the praise-giver was about seven at the time. Unless you're eight, the world really has changed since you were seven. But possibly not as much as you have.

Only marginally less cliched is the idea that the "millennial" generation is full of narcissists – overgrown children, bursting with entitlement, incapable of sensible decisions about love, work or money, because they're convinced that they're so special. It may be true that today's twentysomethings are more narcissistic than 50-year-olds, but when you analyse the data longitudinally, as researchers did in 2010, you find that's because twentysomethings usually are. Narcissism is a developmental stage, not a symptom of the times. Young adults have been condemned as the "Me Generation" since at least the turn of last century. Then they get older, get appalled by youngsters nowadays, and start the condemning themselves.

One culprit here is how desperate we are to see ourselves as the still, calm centre of the universe – fixed lenses, observing a rapidly changing world, but not changing ourselves. (And not only fixed, but omniscient: when the author Elizabeth Wurtzel wrote an essay attacking millennials for not having produced a cultural equivalent of The White Album, it apparently never occurred to her that there might be culture of which she wasn't aware.) In psychology, the term "consistency bias" refers to the well-studied way we'll retroactively adjust our attitudes to avoid admitting to being changeable. Ask students to rate their anxiety before an exam, then to recall those feelings later, and they'll adjust their memories based on their performance: those who did well underestimate their earlier worry; those who did badly overestimate it.

Goldberg and the anti-narcissist brigade – and maybe all of us – may be victims of a bigger, existential version of this: an unwillingness to concede that "who we are" is something rather unstable. There's nothing wrong with a bit of nostalgia. But believing that change happens only to your environment, or other people, makes life harder to navigate: it means you'll always assume it's your spouse, job or city that's not how he, she or it used to be, rather than yourself – thus blinding you to possible solutions when tensions arise. Of course, back in my day, I think most people realised this. But now everything's gone to the dogs. I blame all this newfangled swing music.

[First published in Guardian Weekend magazine. Illustration: Detail from Parkville, Main Street (1933) by Gale Stockwell, photo by Cliff1066 on Flickr.]

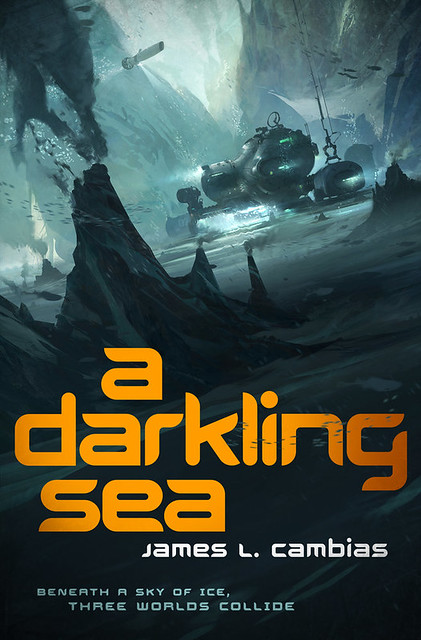

I can say this with some authority: I’ve known longer than anyone else working in science fiction today that James Cambias is a terrific writer. I know this because when I was editor of my college newspaper, James turned in some fantastic articles about the history of the university and of Chicago, the city our school was in — so good that I was always telling him he needed to write more (he had some degree program that was also taking up his time, alas. Stupid degree program). After our time in school, James made it into science fiction and has since been nominated for the Campbell, the Nebula and the Tiptree.

So it comes as absolutely no surprise to me that James’ debut novel, A Darkling Sea, is racking up the sort of praise it is, including three starred reviews in Publishers Weekly, Kirkus and Booklist, and comparisons to the work of grand masters like Robert Silverberg and Hal Clement. He’s always been that good, in science fiction and out of it.

Here’s James now, to tell you more about his book, and how one of the great tropes of science fiction plays into it — and why that great trope isn’t really all it’s cracked up to be.

JAMES L. CAMBIAS:

Small groups of people can have a huge impact on history. The Battle of Bunker Hill was fought by two “armies” which could easily fit into Radio City Music Hall together, without any need for standing room.

I wanted to tell the story of a tiny, remote outpost which becomes the flashpoint for an interstellar conflict. But I had a problem: most of the reasons for interstellar conflicts in science fiction are actually pretty lame.

Seriously: who’s going to fight over gold mines or thorium deposits when the Universe is full of lifeless worlds with abundant resources? And even if we find worlds with native life, it’s fantastically unlikely that humans will be able to live on them without massive technological support.

So there’s not going to be range wars, or fights over the oilfields, or whatever. The sheer size of the Universe makes conflict difficult and unnecessary.

Which means a war with an alien civilization has to be about something other than material wealth. It has to involve the most dangerous thing we know of: ideology.

In my new novel A Darkling Sea, a band of human scientists are exploring a distant moon called Ilmatar. Like Europa, Ilmatar has an icy surface but an ocean of liquid water deep below. The humans have built a base on the sea bottom in order to study Ilmatar’s native life forms, including the intelligent, tool-using Ilmatarans.

But they aren’t allowed to make contact with the Ilmatarans, because of another star-faring species called the Sholen. The Sholen are more advanced scientifically than humanity, and have adopted a strict hands-off policy regarding pre-technological societies. A policy which they insist the humans follow — or else.

That’s all very well, but there’s a problem with that attitude. The native Ilmatarans aren’t passive beings. They are curious and intelligent. One group in particular are very interested in preserving and expanding scientific knowledge, and it’s that band of scientists who come across a reckless human explorer. He winds up advancing the cause of science in a very unpleasant way, and the violation of the no-contact policy inflames the Sholen suspicions of the humans.

The humans resent what they see as bullying by the Sholen. The Sholen suspect the humans have imperialist ambitions. Tensions keep rising and eventually explode into outright war — a war fought by two dozen individuals on each side, at the bottom of a black ocean under a mile of ice.

Alert readers may notice that the ideology which creates this powderkeg in the first place is nothing less than Star Trek’s famous “Prime Directive” — a noble ideal and a hallmark of science fiction optimism.

I’ve always hated the Prime Directive.

The Prime Directive idea stems from a mix of outrageous arrogance and equally overblown self-loathing, a toxic brew masked by pure and noble rhetoric.

Arrogance, you say? Surely it’s not arrogant to leave people alone in peace? Who are you, Cortez or someone?

No, but the Milky Way Galaxy isn’t 16th-Century Mexico, either. The idea of forswearing contact with other intelligent species “for their own good” is arrogant. It’s arrogant because it ignores the desires of those other species, and denies them the choice to have contact with others.

If Captain Kirk or whoever shows up on your planet and says “I’m from another planet. Let’s talk and maybe exchange genetic material — or not, if you want me to leave just say so,” that’s an infinitely more reasonable and moral act than for Captain Kirk to sneak around watching you without revealing his own existence. The first is an interaction between equals, the second is the attitude of a scientist watching bacteria. Is that really a moral thing to do? Why does having cooler toys than someone else give you the right to treat them like bacteria?

“But what if they come as conquerors?” you ask. “That’s not an interaction of equals!”

That’s entirely true. And of course an aggressive, conquering civilization is hardly going to come up with the idea of a Prime Directive. It’s a rule which can only be invented by people who don’t need it.

Which brings me to the second toxic ingredient: self-loathing. I’d say that only post-World War II Western culture could come up with the Prime Directive, as that’s about the only time in human history we’ve had a civilization with tremendous power that’s also washed in a sense of tremendous shame. Previous powerful civilizations felt they had a right, or even a duty, to conquer others or remake them in their own image. Previous weak civilizations were too busy trying to survive. Only the West after two World Wars worries about its own potential for harm.

The Sholen in my novel have that same sense of shame. Their history holds more horrors than our own, and their civilizational guilt is killing them. They’re naturals for a “Prime Directive” philosophy. For them, humans are an ideal object for their psychological projection. They see all their own worst traits in humans, and assume the worst about the motives and intentions of humanity. The result confirms each side’s fears about the other.

As to what happens then, well, read the book.

—-

A Darkling Sea: Amazon|Barnes & Noble|Indiebound|Powell’s

Read an excerpt. Visit the author’s blog.